A 3,600-year-old undisturbed Canaanite burial chamber fit for a king has been unsealed at Tel Megiddo.

Revealing opulent burial goods, the chamber gives invaluable insight into the civilization's funeral customs — and just may shift scholars' conceptions of the era's religious rites.

The surprise find, labelled Tomb 50, was unearthed during the 2016 dig season at Megiddo. Once opened, the mouth of the burial chamber revealed three intact skeletons adorned with gold and silver jewelry. Surrounding the intact skeletons were luxurious grave goods from all corners of the Middle East, and a feast of food offerings for the afterlife. In the back of the masonry-constructed chamber tomb was a "bone heap" of disarticulated relics with six other co-mingled individuals, and some jewelry.

Excavation co-director Prof. Israel Finkelstein was filmed during the exciting exposition of the tomb. His initial reaction was that the impressive burial chamber was obviously used for royalty.

"When you're here," he said to his colleagues, gesturing to the ground, "and the [Bronze Age] palace is 15-20 meters from us, and you don't have 125 [tombs] like these around us, so this may be 'the' nobility. I mean, what else can it be?" asked Finkelstein in a short movie about the 2016 dig season.

Gold torque necklace worn by an adult male buried inside the Canaanite tomb discovered at Megiddo. (Adam Prins)

After unsealing the tomb, the team saw findings which appear to confirm this hypothesis: The archaeologists discovered the intact remains of a middle-aged male bedecked with a skillfully-made gold diadem, along with other well-crafted jewelry. The two other full skeletons on display were also adorned and were of a 8-10-year-old child and a woman in her mid-30s, according to a National Geographic article, which first publicized the new find.

Detail from a gold torque necklace worn by an adult male buried inside the Canaanite tomb discovered at Megiddo. (Adam Prins)

Finkelstein has since dated the untouched tomb to the summit of the Canaanite civilization, the later phase of the Middle Bronze Age (around 1700-1600 BCE). He told The Times of Israel in a recent email it was "easy" to date, based on the vessels discovered in it and those found in the layer above it, dating to ca. 1550-1500 BCE.

Also pointing to the possibility of a royal tomb is the fact that it is adjacent to a Bronze Age palace uncovered in the 1930s. Finkelstein said the chamber "must have been used for a while, perhaps several decades. With the data at hand for now, we cannot say more."

The team will resume excavation there in a few months, during the 2018 summer dig season. Currently, DNA testing is being done on the human remains. The results will be compared with DNA from other tombs at Megiddo, as well as other ancient Canaanite DNA, such as that used in British study released this summer which found that 93 percent of modern Lebanese ancestry comes from the Canaanites.

As to why the tomb was sealed and left untouched after the final three burials, Finkelstein said, "We have no idea. [There was] no clue from the dig, at least not for the time being."

But for the Megiddo Expedition's expert on Canaanite funerary rites, Melissa Cradic, there are many dots that can already be connected to paint a preconception-shattering picture of these "pagans" and their rituals.

Revelation at Armageddon

Known for its apocalyptic name Armageddon (a corruption of the Hebrew Har Megiddo, Mount Megiddo), the northern Israel site hosted a continuously inhabited settlement from 7,000 BCE to circa 500 BCE.

According to Tel Aviv University's Finkelstein, Megiddo appears in "all the great archives of the Middle East." In addition to the Hebrew Bible and New Testament, it is mentioned in Assyrian, Egyptian, and Hittite documents. Even in more modern periods, the ancient military and trade routes were still in use until the end of the Ottoman Empire's rule there in 1918.

A screenshot from a 3D model that depicts the exterior of the Megiddo tomb chamber and corridor before opening. The chamber is visible in the bottom right corner where two large slabs are leaning against each other. (Adam Prins)

"When a site is mentioned in so many historical records, you can make a link between the site and historical processes," said Finkelstein in the 2016 season's video. As an archaeologist who "wished to resolve problems" concerning the historical and archaeological records of the Bronze and Iron Ages, for Finkelstein, "this is the place."

Ahead of his initial excavation season in 1994, Finkelstein wrote about his site choice in a Biblical Archaeology Review article: "Because Megiddo is a cornerstone in the archaeology of Israel, the unresolved issues at the site are in many ways critical for the archaeological and historical study of the entire Levant."

The current bi-annual dig is the fourth scientific excavation of the site. It began in 1994, headed by archaeologists Finkelstein and David Ussishkin. Currently, in addition to Finkelstein, Matthew J. Adams, director of the W.F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research in Jerusalem, is also a co-director of the Megiddo Expedition, as well as Tel Aviv University's Mario Martin.

The team works with experts in subsets of the field of archaeology, including Tel Aviv University's Dafna Langgut (archeobotany), Lidar Sapir-Hen (archeozoology), Meirav Meiri (ancient DNA), and Brown University's Rachel Kalisher (osteology).

Interior of Tomb 50, an undisturbed burial chamber from some 3,600 years ago at Megiddo, looking toward the south corridor. (Robert S. Homsher)

California-based Cradic is responsible for burial rites. Her currently embargoed doctoral dissertation focuses on Canaanite funerary rituals, using recently excavated material from Megiddo.

A gold diadem that adorned the adult male in a 3,600 year old Canaanite burial cave at Megiddo. (Adam Prins)

Back in 2016, she was onsite at the exposition of the intact tomb, which she called an "exhilarating and truly thrilling experience from start to finish… It is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity and we all felt incredibly lucky and privileged to have unimpeded access to such an incredible context."

"The incredible state of preservation of Tomb 50 offers an important opportunity for comprehensive scientific study of the ancient population and their funerary practices. We are studying diet and health, mobility and migration, ancient DNA, organic residues, environment, and issues of identity using the osteological and material remains. We took great care to excavate extremely carefully and to collect samples for a wide range of studies in consultation with specialists at the top of their fields," said Cradic.

In a series of lengthy emails, Cradic enlightened The Times of Israel to the implications of the "royal" tomb's finds in her field of funerary rites.

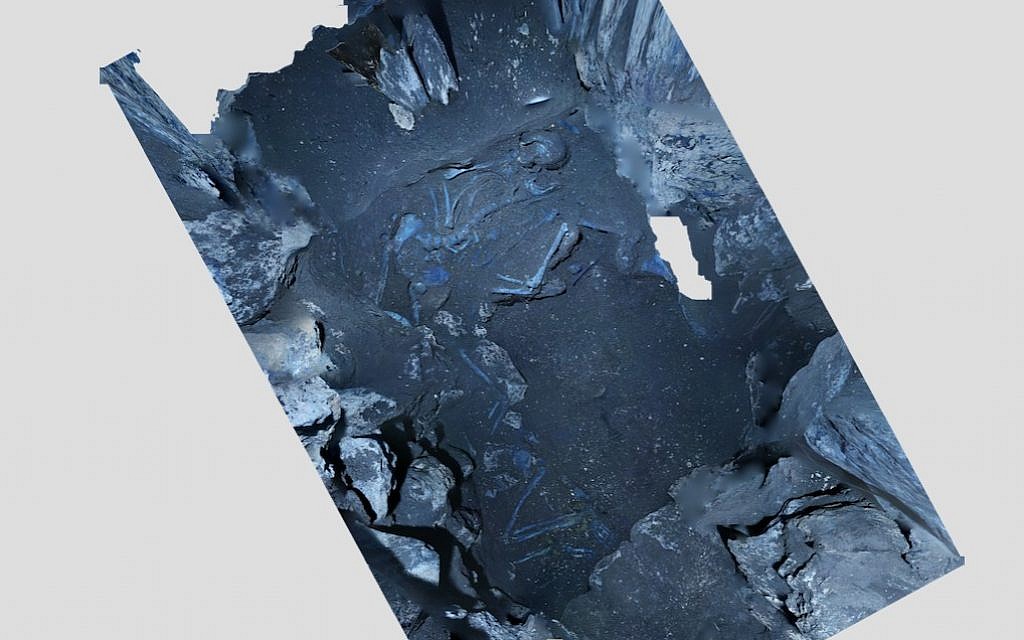

An orthophoto created from a 3D model of an adult male (center) and adult female (bottom) during excavation of the 3,600-year-old burial cave at Megiddo. (Adam Prins and Robert S. Homsher)

Not just a heap of bones

Cradic, whose dissertation is under a publication embargo through 2019, recently published an article, which deals with funerary rituals from a similar "although less elite" tomb at Megiddo, in the Bulletin of the American School of Oriental Research titled, "Embodiments of Death: The Funerary Sequence and Commemoration in the Bronze Age Levant."

The article, based on Megiddo's Tomb 100, is revelatory on a number of fronts, but especially in addressing the significance of "bone heaps" that are found in a number of tombs of the era. Based on several points, including what appears to be the practice of continually moving and displaying relics of the deceased, Cradic writes that these heaps are hardly refuse that was casually "swept away."

Area of excavation at Megiddo before the tomb was revealed. The first stones of the corridor are visible in the right corner behind archaeologist Melissa Cradic. (Adam Prins)

Cradic proposes that, in fact, these bones could represent a life cycle transition in which the deceased passes into the status of "ancestor." The relics of ancestors, as opposed to normative skeletal remains, were regularly used in religious rites.

In her recent article, Cradic writes, "The commingling of skeletal remains represents the end result of a series of highly ritualized, symbolic depositional episodes in which mourners actively handled and removed deceased bodies from their original placements."

A testing ground frozen in time

The intact Tomb 50 gives Cradic an unprecedented chance to observe — Pompeii-like — a burial frozen in medias res.

Cradic said that at the mouth of the chamber, there is "abundant evidence of care and feeding of the dead through food deposits (animal bones, charred organic remains) found in situ in plates and bowls that were positioned carefully near the three intact bodies."

She also describes "relatively dense deposits of fragmented animal bones, charcoal, cooking installations, and imported Cypriot pottery directly above the tomb, which could indicate ongoing commemoration at the grave-site after it was sealed."

Perhaps, much like some Jews who gather together on a yearly anniversary of a loved one's death, these ancient Canaanites also memorialized their ancestors with a graveside meal or ritual.

Decorated bone plaques discovered inside the 3,600 Canaanite tomb at Megiddo that likely covered a box made out of wood or other perishable materials. (Adam Prins)

But it is her theory about the significance of the co-mingled relics that is most interesting. Cradic postulates that the bone heap at the back of the tomb are in the "'ancestor' category for two reasons: (1) the ritualized encounters with the original bodies after burial; (2) the special investment in the construction of the chamber and material assemblage," said Cradic.

In the "royal" tomb, we find what she calls a "ritualized deposition." "The bones became jumbled together due to being moved around within the chamber at least once," said Cradic.

In observing the jumbled relics, she said it is quite possible that they were moved before full decomposition of the flesh.

From observing the physical evidence, Cradic paints a grim, graphic picture of the environment and what took place in Tomb 50, the royal tomb, during its use.

"From the evidence of Megiddo's chamber tombs, it appears that it was an acceptable and perhaps important component of the funerary ritual to interact with corpses before full decomposition. This also allows insight into the conditions of the tomb from the perspective of the survivors, and what they may have experienced in terms of sights, smells, and tactile experiences with the corpses/skeletons."