| GOOD MORNING! What is the secret to happiness in marriage? Here are 3 tips f that with sincerity will help for harmony in marriage. If one's wife is upset with something he did, first, he should admit his mistake and if he isn't sure, he should err on the side of caution and say, "Yes, Dear."

There can't be an argument if one agrees with his spouse. If that doesn't work, he offers an apology, "I'm sorry, Dear." Usually, that helps because a person believes that he or she is right and wants that recognition from others, especially his or her spouse. And if his wife is still upset, he should just explain, "I'm only a man" ... hoping that it will bring out the natural compassion and forgiveness for those who see the error of their ways. We are all fallible. By admitting that one is not perfect and makes mistakes, it can ameliorate the anger.

In truth, marital happiness starts much earlier with whom you choose as your spouse. Our forefather Avraham sent his servant, Eliezer, a long distance to Haran to choose a wife for his son, Yitzhak, Why? The people of Canaan were idol worshippers and the people of Haran were idol worshippers. What was Avraham seeking by choosing a daughter in law from the people of Haran? Avraham knew that those living in his old country were raised with respect for people and taught to do kindness. Sure, the people may be idol worshippers, but education can correct mistaken ideologies. However, character traits are imprinted at a very early age and they are very hard to change.

There is a seemingly strange verse in the Torah regarding love and marriage. The Torah tells us, "He (Yitzhak) married Rivka, she became his wife, and he loved her" (Gen. 24:67). Isn't the "natural" order of life that one loves another person ... and then marries her or him? The Torah is giving us a great insight: Real love is developed after making a total commitment to one's spouse. Love is the pleasure one has in focusing on the good in someone else. With total commitment, one will be sure to see those virtues.

We all want love and we seek someone who will make us happy. What often passes for love is infatuation and blind passion ... or at best, self-centered love. What we have are two self-centered people looking to make themselves happy. Without that total commitment, then if one's spouse does things that upset you or one thinks there is someone else who can please him or her more -- then there is a breakdown of the relationship.

Love has to transcend the self-centeredness to the realization that true and greater happiness comes from doing for one's spouse, rather than using one's spouse as a means for one's own gratification. For that to happen, the commitment must be total. Rabbi Noah Weinberg, of blessed memory, used to liken the commitment to one's spouse to the commitment one has to his own hand. One does not cavalierly chop off his hand because it displeased him. However, there is a time when he will have it amputated -- when it has gangrene and threatens his life.

We need to understand that marriage is a means, not a goal. A depressed, aimless, lonely single person will likely end up in marriage as a depressed, aimless, lonely married person. The Torah teaches us that Adam, the first man, was completed by marrying Eve (Chava): "a man shall ... cling to his wife and they shall become one flesh" (Gen. 2:25).

One has to figure out what he values in life, what he wants in life -- and then look for someone who has the right character traits of kindness and truth and who has the same values.

According to the Torah, the purpose of a marriage is to create an entity that will grow one's relationship and closeness with the Almighty -- and to raise children through whom they can transmit the legacy of a Torah way of life.

Whatever one's goals, he must choose a spouse with good character who has the same values and goals. Then with total commitment there is hope for great happiness!

Love Yehuda Lave

I'm much thinner now, but on this server that I send the email, it is hard to put on a new picture |

|

|

|

Monday, 18 March 11:03 AM Monday, 18 March 11:03 AM | | | From ISRAEL21c "Adloyada" is a contraction of the phrase "ad lo yada" or "unable to differentiate," referring to the Purim tradition of drinking into oblivion. Adloyada is also the name of the historic Purim parade that originated in 1900s Tel Aviv and helped to cement that city's reputation as Party Central. The first Purim parade was instituted in March 1912 by Avraham Aldema, a painting teacher at the Herzliya Gymnasium high school. It featured costumes based on themes from the Megillah (the Purim story), the Bible, Jewish history and life in the Land of Israel. The procession marched from the gymnasium down to the railroad track on Herzl Street, accompanied by a band of merrymaking young people, workers and artists that included Aldema, known as Hevre Trask ("noisy folks" as "trask" means "crash" in Yiddish). Meir Dizengoff, then head of the Tel Aviv's founding Ahuzat Bayit society (and eventually the first mayor after Tel Aviv received township status), decided that the parade should become an annual event. A committee was formed to select a name for the Purim carnival and 253 names were submitted from locals and outsiders. The name chosen, "Adloyada," was offered by the poet, author and newsman Isaac Dov Berkowitz who based it on an excerpt from the Babylonian Talmud stating that on Purim, one must drink wine until one does not know the difference between accursed Haman and blessed Mordechai.

Baruch Agadati, crown prince of Tel Aviv night life, with Zippora Zabari, winner of the "Queen Esther" contest of 1928. Photo courtesy of National Library of Israel It was also in the 1920s that dancer-choreographer-artist and Tel Aviv's original man-about-town, Baruch Agadati, became involved in the festivities, organizing an annual Purim ball and instituting the Purim Queen pageant. (Read here

about the Yemenite milkmaid who became 1928's Purim Queen.) The competition between the celebrations — and the fact that Agadati wore fine clothes and charged entrance fees to his parties – led to a not-so-friendly rivalry between the bon vivant and the bohemians. Hevre Trask made their feelings known in print, leading to a lawsuit filed by Agadati charging Trask with defamation of character. Initially, the Purim parades were sponsored by the Jewish Workers' Fund of the Mapai (Labor) Party (from 1921-1925) and then by the Jewish National Fund (from 1925-1928), after which Aldema turned to the municipality for funding. The procession of 1929 was jointly sponsored by the JNF and the municipality. In 1930, there was no Purim procession following the riots and massacres of 1929. In 1931, the Tel Aviv Municipality took over the Purim parade that was officially named "Adloyada" in 1932. According to a Tel Aviv Municipal Archive essay, a special committee of artists, writers, architects and theater people was formed "to give the Adloyada processions historical content and a worthy artistic level." Among the topics selected were "settlement, construction, agriculture, testimony, immigration and even the rise of anti-Semitism in Europe." As part of the Purim events, the city's houses and vehicles were decorated with flowers, carpets and flags, and colorful lighting was installed. Marchers were guided by director Moshe Halevi and musician Menashe Rabina, with decorations around the city by leading artists like Nahum Gutman and Reuven Rubin.

A 1935 float in the Tel Aviv Adloyada Purim Parade depicts the biblical story of Esther. Photo courtesy of GPO The parade never shied away from current politics, represented in floats like the one in 1926 that buried the British Mandate in a coffin, the 1933 float of Hitler holding a lance aloft before two corpses with the sign "Death to All Jews," the three-headed dragon representing the Nazi regime in 1934, or the 1935 anti-profiteering crocodile. Interestingly, in 1933, the German Consulate in Jerusalem wrote to the mayor of Tel Aviv demanding an apology but Dizengoff refused, reportedly responding that it was amazing the critique wasn't stronger.

Unemployed workers march in the 1934 Adloyada Parade. Photo courtesy of GPO The Adloyada came to an end in 1936. As the Tel Aviv Municipal Archive essay speculates, "The official reason given was the difficult situation of German Jewry and of Central and Eastern European Jewry, as well as [curfew] decrees by the British Mandatory authorities. It is also possible that budgetary difficulties and illness and death of Dizengoff in 1936 caused a stop to the processions." Following the establishment of the State of Israel, the Adloyada tradition was renewed and Tel Aviv hosted the parade from 1955 through the late 1960s. The parade was transferred to Holon in the 1970s.

Adloyada floats never shied away from politics. This 1956 float shows an imaginary prime ministerial summit between Israel's David Ben-Gurion and Egypt's Gamal Abdul Nasser. Photo courtesy of GPO In the early 1980s, the Tel Aviv Adloyada tradition was revived by the Sheinkin Street avant garde. The tone was far more in the spirit of Hevre Trask: a punk rock/performance art street fair that went on for days. But, like the fast and furious music that inspired it, the Sheinkin Adloyada bacchanal came and went.

The avant garde Sheinkin Adloyada of the early 1980s. Photo courtesy of GPO In 1998, a one-time Adloyada was held in Tel Aviv that was documented in a video that jokingly opened with the line: "The Last Tel Aviv Adloyada – 1998. The next Tel Aviv Adloyada will probably be in 2228"

A 1998 Adloyada float featuring David Ben-Gurion. Photo courtesy of GPO Today, the word coined by Isaac Dov Berkowitz, "Adloyada," has come to mean any Purim parade held in towns across Israel. As for Tel Aviv, its reputation as Party Central holds fast – just wait for Eurovision in May. | |

|

|

When Automobiles were Art | | 1921 Farman A6B Torpedo Sports | |

| | | 1922 Marmon 34BSpeedster | |

| | 1929 DuPont Model GSpeedster | |

| | 1930 Isotta Fraschini-87A SSTorpedo Sport | |

| | 1930 Ruxton Model C Raunch and Lang Roadster | |

| | 1931 DuPont Model H Merrimac SportPhaeton | |

| | 1932 REO Royale ConvertibleCoupe | |

| | 1933 Hispano Suiza J12 Cabriolet DeletrenFreres | |

| | 1936 Delahaye 135 Figoni and Falaschi CompetitionCourt Cup | |

| | 1936 Delahaye 135 Figoni etFalaschi Torpedo Cabriolet | |

| | 1937 Delahaye 135 Figoni etFalaschi Torpedo Cabriolet | |

| | 1938 Horch 853A Erdmann & Rossi Sport Cabriolet | |

| | 1939 Delage D8 120S Letourneur and Marchand AerosportCoupe | |

| | 1939 Delahaye 165 Figoni and FalaschiCabriolet | |

| | 1948 Delahaye 135 M Figoni and FalaschiCabriolet | |

| | 1949 Delahaye 175 S SaoutchikRoadster | |

| | 1949 Lancia Aprilia Pinin FarinaCabriolet | |

| | 1953 Allard K3 Roadster | |

| | 1953 Siata 208S Spyder Bertone | |

| | 1954 Chrysler Ghia Special G1 | |

| | 1964 Bizzarrini 5300 Corsa | |

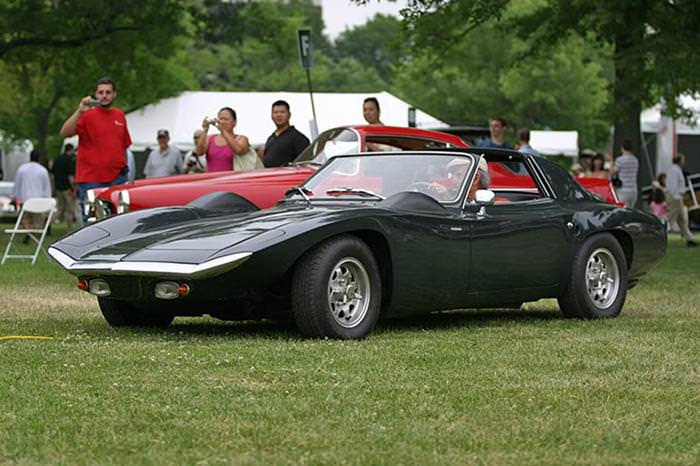

| | 1966 Finch Phoenix | |

| | 1947 Morgan Roadster F Super 3 Wheel | |

| | 1925 Rolls-Royce Phantom I AerodynamicCoupe | |

| | 1925 Rolls-Royce Phantom I Aerodynamic Coupe, rearview | |

| | 1938 Phantom Corsair | |

| | 1953 Alfa Romeo BAT 5 Concept Car | |

| | 1937 Delahaye135MS | |

| | 1951 Bugatti Type 101 Ghia Roadster | |

| | 1953 Chrysler Ghia Coupe GS-1 | |

| | 1954 Buick Wildcat II | |

| | 1954 Siata 208S Vignale Coupe | |

| | 1934 Voisin C15 Roadster Saloit | |

| | | | | |

|

|

14 Facts About the Code of Jewish Law (Shulchan Aruch)  1. Its Hebrew Name Means 'Set Table' The Talmud contains 2,711 densely packed pages, full of involved discussions on all matters of Jewish law. In the years following its completion, countless comments, questions, and explanations were added by the various commentaries. Known in Hebrew as Shulchan Aruch ("Set Table"), the Code of Jewish Law lays out practical and concise instructions culled from the intricate web of Talmudic deliberation and rabbinic commentaries that come along with it. 2. Its Current Form Is a Hybrid of Seperate Texts Authored By Two Men Who Never Met The Shulchan Aruch was written by Rabbi Yosef Caro (1488-1575), a Sephardic sage who lived in the holy city of Safed, in the north of Israel. At the same time that Rabbi Caro was completing his work, Rabbi Moshe Isserles, an Ashkenazi rabbi in Cracow, Poland, was working on a similar project. Upon seeing the work of the Sephardic scholar, Rabbi Moshe chose to discard his manuscript and add glosses to the already-released text instead. He also notes wherever Ashkenazic tradition differs from the rulings codified by Rabbi Caro. Thus, a unified text was able to be used by all segments of the Jewish world. The first page of the Cracow edition of the Shulchan Aruch, which also incorporated the glosses of the Mapah. 3. The Commentary Is the 'Cloth' Keying off the name Shulchan Aruch, Rabbi Moshe called his commentary Mapah, which means "tablecloth." In the words of his introduction: "I have come after [Rabbi Caro] to spread a cloth over the set table, upon which he has collected all the delightful fruits and delicacies that a person may love. For without this [addition], the table he has set before G‑d was not placed before the people of these lands…" 4. It has Four Parts Rabbi Caro structured his work to mirror the Arba Turim ("Four Rows") written by Rabbi Jacob ben Asher. It comprises four books, each dedicated to another area of Jewish life: - Orach Chaim (Way of Life) covers prayer, Shabbat and holidays, and other issues encountered in the day-to-day.

- Yoreh Deah (He Shall Show Understanding) includes the intricate laws of kosher, usury, vows, and other areas in which a rabbi is generally consulted.

- Even HaEzer (Stone of Assistance) contains laws of marriage, divorce etc.

- Choshen Mishpat (Breastplate of Justice) is devoted to monetary laws, torts, and other issues relevant to a rabbinic court.

The first page of the Shulchan Aruch, printed in Venice during the lifetime of the author. 5. It Was Not Intended to Be a Primary Source The author of Shulchan Aruch never intended that the work be used in isolation. Rather, he hoped that it would serve as a review for students of his lengthier commentary, the Beit Yosef, where the background and discussion behind many of his rulings are found. 6. It Was Controversial In Its Day When the Code of Jewish Law was first released, it received criticism reminiscent of the complaints lodged against Maimonides' Yad Hachazakah. The fear was that people would become lazy, only consulting the sparse rulings of the Code, without bothering to understand the copious scholarship and nuance that stands behind every line. There was also the initial concern that Rabbi Caro had based his rulings primarily on the teachings of Rabbi Isaac Alfasi (Rif), Maimonides, and Rabbi Asher ben Yechiel (Rosh), and did not represent the scholarship of the broader Jewish community. This concern was greatly assuaged by the glosses Rabbi Moshe Isserles added. 7. It Was First Printed in Venice in the 1560s The first printing of the Shulchan Aruch was produced in Venice in approximately 1566, and included just the work of Rabbi Yosef Caro. The first edition to contain the teachings of both rabbis was printed in Cracow in 1578 (or earlier). A modern set of Shulchan Aruch with commentaries contains many, many volumes. 8. It Begins With a Wake-Up Call The first book of the Code of Jewish Law begins with the following exhortation: "He shall strengthen himself like a lion to rise in the morning to serve his Creator, Who wakes the dawn." Rabbi Moshe adds a qualifying note, that at the very least one should not sleep past the time of communal prayers. 9. It Contains Both Rashi Script and Regular Script In the original Cracow edition, which included no commentaries, the words of both rabbis were printed in Rashi script, with the words of Rabbi Yosef Caro appearing slightly larger. In the standard editions of centuries since, Rabbi Caro's words are printed in standard block script, with the additions of Rabbi Moshe Isserles in Rashi script, allowing the reader to easily discern between the two. 10. The Code Is Now Surrounded by Commentaries Many commentaries have been written on the Code of Jewish Law. Some of the most prominent ones have been printed on same page as the Code itself, including: - Turei Zahav (Taz) by Rabbi David Halevi Segal (1586-1667) on the entire work.

- Magen Avraham by Rabbi Avraham Abbale Gombiner (1637-1682) on Orach Chaim.

- Siftei Kohen (Shach) by Rabbi Shabtai Kohen (1622-1662) on Yoreh Deah.

- Ketzot Hachoshen (Ketzos) by Rabbi Aryeh Leib Heller (1745-1812) on Choshen Mishpat.

- Ba'er Hetev summarizes the rulings of prior commentaries on the Shulchan Aruch.

The first page of a standard edition of Shulchan Aruch, with the text surrounded by the classic commentaries. 11. The Alter Rebbe Wrote One In response to a request from his mentor, Rabbi Dov Ber, the Maggid of Mezritch, the Alter Rebbe (1745-1812), founder of Chabad Chassidism, composed his own version. Commonly known as Shulchan Aruch Harav, it takes into account the rulings of the Shulchan Aruch and many others, most notably the Magen Avraham. Although it follows the chapter divisions of Rabbi Caro's work, the text is entirely reworked and significantly longer. Learn the Alter Rebbe's Shulchan Aruch in Hebrew and English 12. The Kitzur Shulchan Aruch Is Not an Abridgement Rabbi Shlomo Ganzfried (1804-1886) wrote the very popular Kitzur Shulchan Aruch. Although its name means "Abridged Shulchan Aruch," it is actually an original work, which clearly and succinctly spells out the basics of Jewish law in a manner that is easy for the layperson to understand. Rabbi Shlomo Ganzfried, author of the Kitzur Shulchan Aruch. 13. Mishnah Berurah Is a Popular Commentary Rabbi Israel Meir Kagan (known as the Chafetz Chaim, 1839-1933) wrote a commentary to the Shluchan Aruch called the Mishnah Berurah ("Clear Study"). Printed along with the text of Orach Chaim, it fills six volumes. 14. It Is Synonymous With Jewish Law Although the totality of Jewish law is much broader than the Shulchan Aruch, the name has become synonymous. Hence, when one wishes to describe a Jew whose every move is in sync with halachah, one could use the moniker, a "Shulchan Aruch Yid."  Rabbi Menachem Posner serves as staff editor at Chabad.org, the world's largest Jewish informational website. He has been writing, researching, and editing for Chabad.org since 2006, when he received his rabbinic degree from Central Yeshiva Tomchei Temimin Lubavitch. He resides in Chicago, Ill., with his family. © Copyright, all rights reserved. If you enjoyed this article, we encourage you to distribute it further, provided that you comply with Chabad.org's copyright policy. You may also be interested in... The Alter Rebbe's Shulchan Aruch - Code of Jewish Law Halachah from Kitzur Shulchan Aruch Join the Discussion The shach also has a commentary on choshen mishpot he also wrote a commentary on Orach Chaim however it was lost Reply Todah! I didn't know the Alter Rebbe had written one. Reply Shinheim outside US March 7, 2019 great article! Reply Amazing! May we regard Torah as the standard Reply Excellent. Thank you Reply These are great lists of interesting pieces of information, Thank you! Reply |

|

|

See you tomorrow

Love Yehuda Lave |

|

|

| | | |

| | | | | |

|  |

|

| |

|