It's either an intricate forgery, or the archaeological find of the decade. A team of scholars of the ancient Luwian language have deciphered a 29-meter-long hieroglyphic inscription from the Late Bronze Age more than 3,000 years ago, which is the only contemporary account of the fall of the Hittite Empire and the rapacious conquering of the biblical "Sea Peoples" as far south as Ashkelon.

And the back story of what may prove to be a missing link in the understanding of Levantine civilization is equally interesting.

Only in June of this year, Swiss geoarcheologist Dr. Eberhard Zangger, president of the Luwian Studies foundation, was made aware of a 15-centimeter stack of documents — illustrations and translation notes — about the limestone frieze which was originally found in 1878 in the village of Beyköy, approximately 34 kilometers north of Afyonkarahisar in modern Turkey.The longest known hieroglyphic inscription from the Bronze Age has disappeared, however, and is said to be under lock and key in a Turkish national collection at an undisclosed location. What remains is an illustration copy created by the French archeologist Georges Perrot based on stones retrieved by local peasants during the 1878 dig. Subsequently, the villagers apparently used the stones as the foundation of their local mosque.

In the 1950s, the inscription resurfaced when a joint Turkish-United States team of Luwian scholars sat to translate the myriad inscriptions which had been found in the 19th century and had sat in the Ottoman Empire collections. The scholars' team disbanded in 1984 and their findings were never published. As they died, their work was almost forgotten.

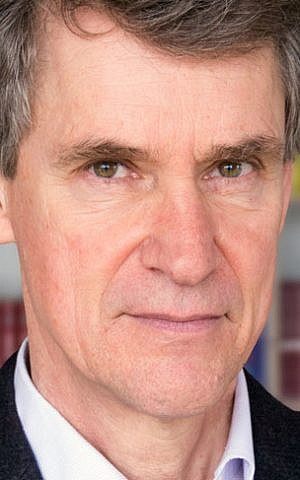

Geoarchaeologist Dr. Eberhard Zangger, president of the Luwian Foundation. (courtesy)

In 2012, the final scholar, the English prehistorian James Mellaart died. While desposing of his estate, son Alan found the documents surrounding this inscription and gave them to Zangger in June. A first publication in the TALANTA archaeological journal based on initial findings is due to be published in December. There, Zangger and the Dutch linguist and Luwian language expert Dr. Fred Woudhuizen "will present a transcription, a translation, a detailed commentary, and the remarkable research history of the find," according to a press release from the Luwian Foundation.

In a brief conversation with The Times of Israel, Zangger emphasized that there's an unfinished argument over whether the inscription is authentic or not. While more research is needed, especially since the original frieze is unavailable to scholars, he said, "We think it's too long and complicated and grammatically correct to have been forged by anybody."

In terms of its significance, the frieze is unprecedented: "If it's authentic, it means there is a contemporary account of what happened during the collapse of the Hittite civilization," said Zangger.

According to the scholars, the inscription was commissioned by the Great King of Mira, Kupanta-Kurunta, who ruled a Late Bronze Age state in western Asia Minor. Circa 1190 BCE, Kupanta-Kurunta ordered his armies to invade the vassal states of the Hittites in the east.

According to the press release, "After successful conquests on land, the united forces of western Asia Minor also formed a fleet and invaded a number of coastal cities (whose names are given) in the south and southeast of Asia Minor, as well as in Syria and Palestine… The Luwians from western Asia Minor advanced all the way to the borders of Egypt, and even built a fortress at Ashkelon in southern Palestine."

The Sea People advanced all the way to Ashkelon and built a fortress

Zangger told The Times of Israel, "There are 150 place names mentioned in the text, 50 of those can be identified today." Ashkelon, he said, is likely the only Palestine-based city mentioned in the inscription.

"The Sea People advanced all the way to Ashkelon and built a fortress there," he said.

A 10th-9th century BCE burial in the excavation of the Philistine cemetery by the Leon Levy Expedition to Ashkelon. (Tsafrir Abayov/Leon Levy Expedition)

Who the "Sea People" are, he said, is a matter of interpretation. Some consider them the biblical Philistines. In Hebrew, they are called "Plishtim" (or invaders) in the Bible. There is a contemporary Egyptian record of an invading people called "Peleset," said Zangger. Some scholars identify this people as the Philistines, but he is "agnostic" about this issue.

"I think that the models we have used from the past [for the Philistines], we can see from the documents, are too simplistic, but we need more time to analyze," said Zangger.

Unfortunately, said Zangger, there are no other accounts after 1193 BCE of this civilization. "This the first."

But potentially not the last: the pile Zangger was given in June includes other illustrations of inscriptions which have not yet been translated. While they have no solid photographic evidence disproving forgery, "according to the sources what is shown in these documents actually exists in Turkey," he said.

If proven authentic, this trove represents "one of the most special finds in archaeology today," said Zangger.

This famous scene from the north wall of Medinet Habu is often used to illustrate the Egyptian campaign against the Sea Peoples in what has come to be known as the Battle of the Delta. Whilst accompanying hieroglyphs do not name Egypt's enemies, describing them simply as being from "northern countries", early scholars noted the similarities between the hairstyles and accessories worn by the combatants and other reliefs in which such groups are named. (Seebeer / Wikipedia)