ORADEA, Romania — On a neglected stretch of road not far from the compound housing the bulk of Oradea's Jewish infrastructure lies a dull brick building. Above the entrance is a small sign in stereotypical "Jewish" typeface. "Kosher," it reads meekly, and below that, "Wine. Coffee. Jazz."

With its graffiti-covered facade, the place hardly resembles a jazz club — but neither does it look like an old Vizhnitz synagogue. And though it's still labeled as such on Google Maps, the building hasn't been prayed in for over 80 years.

The city of Oradea, with a Jewish population hovering somewhere around 400, might not have the numbers to necessitate a kosher jazz bar, or to keep one afloat, but Jews don't seem to be its niche audience: The handful of grungy-looking hipsters lounging in the courtyard are likely not familiar with the ancient dietary laws.

Exterior of the kosher jazz bar and independent theater in Oradea. (Courtesy)

On a sunny day in early autumn, they recline easily beneath umbrellas on oversized chairs that look more like mattresses as ambient trance music drifts from the bar inside. A young couple talks quietly while the barman lounges nearby smoking a cigarette.

The bar's owner, Andris Sella, says that the property which he now rents from the Jewish community has a troubling history, and has changed hands more times than the city itself. A mean feat: Oradea was in turns ruled by Turks, the Austro-Hungarian empire, and the Soviets, among others, before becoming part of modern-day Romania.

A group of Vizhnitz Hasidim visiting the site of the synagogue built by their sect in 1933, and abandoned in 1936 before the Holocaust. (Courtesy)

"This was originally a synagogue built by the Vizhnitz Hasidic sect in 1933," he says, "though they only used it for three years before fleeing due to the rising anti-Semitism prior to World War II."

Sella says that when Oradea was taken over by the Nazis, the fascist Hungarian Arrow Cross militia used the building to torture the city's Jews in an attempt to root out any hidden valuables. Shortly thereafter, it was converted into a hospital for the remainder of the war.

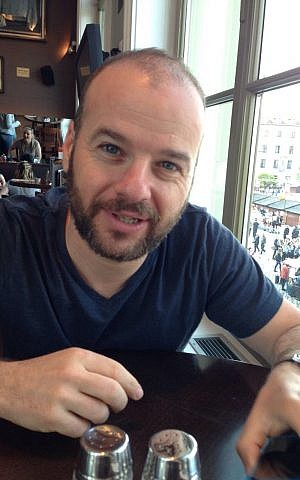

Andris Sella, owner of Oradea's kosher jazz bar and independent theater. (Courtesy)

"When I got it, the building was a furniture factory," Sella says. "It had been a manufacturing place since the late '40s."

Sella says that it wasn't initially his intention to have a jazz club here, but things just sort of fell into place.

"I've been importing wines from Israel since 2007," says the 40-year-old Jewish Oradean. "At first, I just used the large empty space where the synagogue used to be as a warehouse to store the wines."

"Where the bar is now, we used to just sell coffee, but then we wanted a place where people could sample the wines," he says, "so they started gathering in there for tastings."

Sella says that he used to own a popular club in the city's center, which he sold in 2013. After the front of the synagogue started being used for wine sampling, it was soon converted into a full-time watering hole.

"I guess I just had it in my DNA to have a bar," he says. "And from there it went from wine to jazz — I like jazz music, and wine and jazz always go together, so that part was natural."

Equally natural was Sella's decision to enter the Israeli wine market — the distributor of Israeli and kosher wines throughout Eastern Europe moved to Israel in 1997 at age 19, and holds Israeli citizenship.

The interior of the small kosher jazz bar in Oradea. (Yaakov Schwartz/Times of Israel)

He had to return to Romania three years later when his mother suffered a terminal illness, but he says he still visits Israel two or three times a year, and has family in Safed.

"I wanted to move there because I'm a Jew," Sella says.

"I had visited Israel when I was a kid with my parents, and I was familiar with it. And growing up, my family was active in the Jewish community, we'd celebrate the holidays — I was even in the choir as a kid, even though I have no voice. So you know, I love Israel and I'm connected to it. I'm drawn to our ' aretz,'" he says, using the Hebrew word for land.

After introducing the live music, Sella decided to open up his business to other creatives as well. He began storing his wines elsewhere and turned the larger space into a place for artists to display their work.

Exterior of the independent theater in Oradea. (Courtesy)

"I wanted the place to be dedicated to culture. So first we started with photo expos, and after that painters slowly started to come to display their works, and then we had piano nights and violin nights. And then the young actors wanted a place to work besides the State Theater," he says.

Sella let the artists, and later on, the theater performers, use the venue for free — a gesture that was more than symbolic.

"I had to pay the rent, and of course the other bills: heating in the winter, electricity, water. It was expensive, but I think it was worth it," he says.

The move paid off in the end. The space eventually came to be used exclusively for acting, and is now a nationally-known venue and draws thespians from all over the country.

Actors do a table read in Oradea's independent theater. (Courtesy)

"The independent theater helped put the place on the map," says Sella. "I don't think the jazz bar would have made it on its own."

These days the artists pay a small percentage of their nightly take to help cover overhead. Still, Sella says that whatever costs aren't covered he pays out of pocket — though he doesn't seem regretful. He's quick to kvell about the current project taking place, the theme of the young actors and directors revolving this year around the difficult relationship between Romania and neighboring Hungary, as well as life under Communism in the not-so-distant past.

Sella would like to tell more Romanian Jewish stories, and is planning a Jewish theater festival this upcoming Passover if he can get funding.

Exterior of the kosher jazz bar and independent theater in Oradea. (Yaakov Schwartz/Times of Israel)

He says that the city has an incredibly rich Jewish history, and that before the Holocaust over one-third of the city's 90,000 residents were Jewish.

"We built this city," he says.

He also describes the difficulty with which the Jewish community recovered their stolen property, many decades after the war.

"It was very hard work to get it back, and they gave it very late, so many people had died by then, or moved elsewhere, and never got their property back," he says.

With national attention on the studio and the work coming out of it, Sella has a grand vision for the venue's future, and would like to see the space developed into a full cultural center hosting multidisciplinary expositions that would include music, sculpture, painting, and more.

"I want to attract European funds to do something like that — it's a challenge, and will take a lot of money to renovate the place, but the Jewish community is on my side," he says.